By Sanjaya Jayasekera.

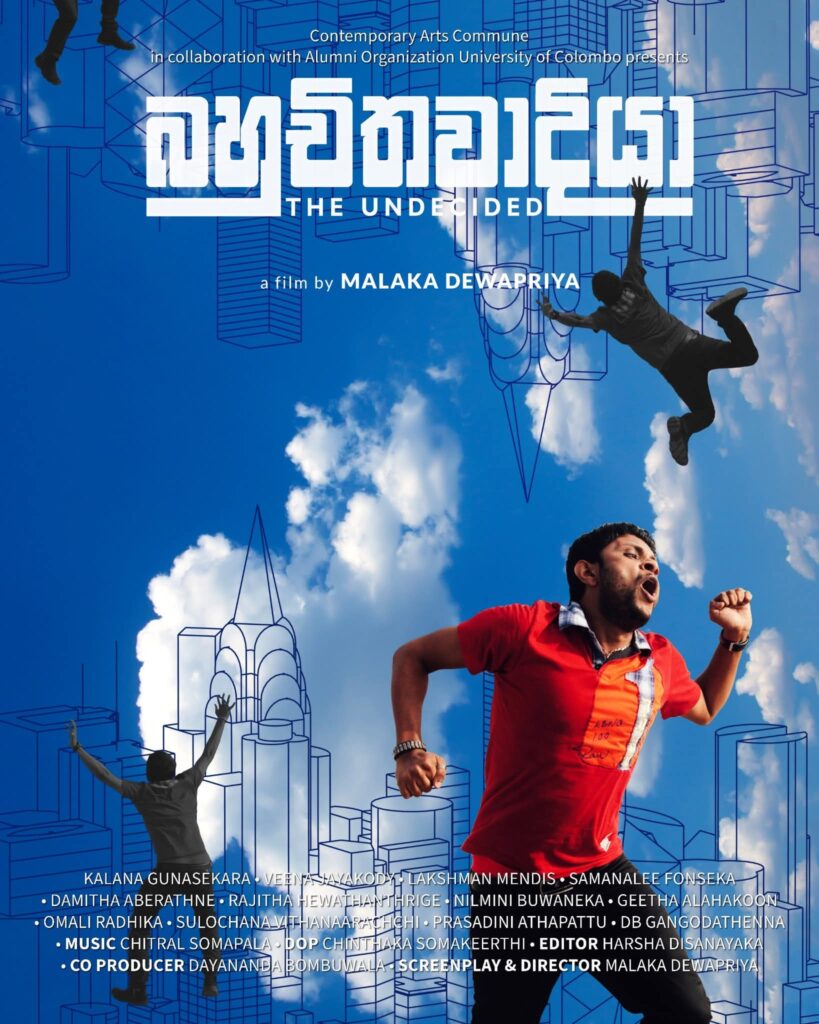

Malaka Dewapriya’s film Bahuchithawadiya (The Undecided) is an ambitious but ultimately disoriented work that attempts to offer a portrait of the youth adrift in post-civil-war urban Sri Lanka. The film takes the form of a character study, which according to Director’s own introduction, “presents a reflection of the youth of this time, who are searching for easy ways to survive due to lack of job security and are immersed in the dream of escaping this country, using social media, smartphones, and iPhones to achieve their old dream, and making all connections their victims.”

The film has garnered attention for its experimental tone and portrayal of alienation among the impoverished unemployed – jobless or precariously employed and exploited in the gig economy – youth in Colombo. However, beneath its cinematic form, the film offers a bleak, superficial depiction of social decay and a disheartening and ultimately reactionary indictment of working-class and unemployed youth—not as victims of capitalism, but as the agents of their own moral downfall.

The protagonist, Sasitha (Kalana Gunasekara), is a delivery worker in Colombo, the industrial capital of the country. He is employed under precarious conditions by a miserly boss. With no prospects for economic or social mobility, Sasitha turns his attention to seducing women online—married, unmarried, older, younger—all in the hopes of securing a visa to a European country or gaining some financial benefit. His duplicity and exploitation of these women are portrayed not as unwilling and temporary predatory responses to a brutal economic system but as intrinsic and permanent features of his character. What emerges out of him is not a layered human being, but a cypher of cynicism and indecision. Herein lies one of the film’s most serious failings: the absence of any serious attempt to explain the portrayal of Sasitha’s behavior through the social forces and material conditions in which he lives.

Dewapriya has captured certain surface features of social life. The film presents a series of acidic behaviours—adultery, betrayal, cheating, exploitation, desperation—yet none are given sustained focus or examined in depth to reveal their underlying contradictions. As a result, the viewer is left with a collection of symptoms, rather than an understanding of the social reality that gives rise to them. This is not merely an aesthetic or artistic shortcoming, but a deeply ideological one. An artist does not simply replicate life; he is not a photographer. He bears the responsibility of discovering truth. By isolating Sasitha’s personal corruption from the real world that produces it and stands in contradiction to it, Bahuchithawadiya, despite its claims to realism, ultimately proves to be profoundly evasive and dishonest.

It is not enough to show that a character, representing “contemporary youth”, is indecisive, manipulative, and amoral. One must ask: why? What has shaped this poisonous character? What forces act upon him? Who is responsible for his life? Is his behaviour inevitable? Dewapriya seems uninterested in these questions. The result is a film that verges on character assassination. Sasitha is not portrayed as a victim of the capitalist system, nor as someone with even the faintest sense of resistance to its injustices. Instead, he appears as its willing accomplice—both seeking to benefit from its corruption and attempting, paradoxically, to escape its consequences. In the final analysis, he is shown not as someone shaped by a toxic social order, but as one of its architects. “The youth”, as we have known it, has ceased to be!

The viewer is invited to conclude that the crisis of contemporary youth lies in their own character: their indecision, their dishonesty, their lack of conviction. This is an old slander, repeated countless times by the middle class and its intellectual spokespersons, who recoil in fear at the sight of the impoverished, unemployed, and restless young. That this view should find cinematic expression in a country that in 2022 witnessed one of the most significant mass uprisings of youth in recent history is both telling and damning. Ultimately, the youth does not happen to find their class enemy.

The film’s final scene shows Sasitha mechanically resuming his practice of seducing women online, without the slightest remorse—even after having been caught red-handed in his previous deceptions. This serves as a conclusive testament that the filmmaker is less concerned with exploring the real social and psychological dynamics shaping youth behavior, and more intent on confirming a middle-class ideology that views oppressed youth as inherently selfish, untrustworthy, incorrigible, and erratic.

The film’s central concept—”Bahuchithawadiya”—suggests a permanent, innate condition of moral and psychological ambiguity. This is entirely ahistorical and unscientific. The youth of Sri Lanka are indecisive not because they are naturally cynical or morally bankrupt. They are uncertain because their lives are uncertain: jobless, underpaid, precariously housed, exploited. The labor market offers no security. Political parties offer no hope. Trade unions have betrayed them. Their so-called indecision is not a failing; it is a symptom of a broader social crisis.

Indeed, the idea that Sri Lankan youth are fundamentally morally degraded is refuted by events themselves. In 2022, tens of thousands of young people took to the streets in an unprecedented mass uprising, protesting the unbearable cost of living, fuel shortages, authoritarian repression, and the corruption of the ruling political establishment. This movement did not emerge suddenly from a generation lost in nihilism, but from a population forced to resist and confront the consequences of decades of neoliberal policy and imperialist subjugation.

To assert, as the film does, that youth have no direction because, in the backdrop of a predatory economy, they are inherently flawed, is to participate in a reactionary ideological project. Dewapriya offers the youth no future and no past. They are merely floating signifiers of decay, cynicism, and amorality. They are uninfluenced by any sense of resistance, struggle, solidarity, or political awakening. Even in Colombo, the epicenter of industry and protest, Sasitha never encounters a strike, a rally, or even a conversation that hints at collective resistance. There is not even a passing allusion to conscious class war measures–austerity, privatization, debt crises, or the militarization of public life following the end of the civil war—realities that are inescapable features of everyday life in the country. The working class —despite its overwhelming presence and historical importance—is nowhere to be found. Instead, we are shown a hermetically sealed world of urban apartments and transactional relationships, in which everyone is either a victimizer or a dupe.

Sasitha flicks through television channels airing religious sermons, astrology segments, and reality shows—programs ostensibly meant to shape the youth—but never news, politics, or protest. The enemy is distant, and the struggle is futile. This is no accident, but a deliberate artistic choice—one that lays bare the filmmaker’s class perspective.

Class struggle is the highest expression of both class resistance and solidarity—one that leaves no room for pettiness, selfishness, or moral cynicism. It imparts to working-class youth a profound sense of social responsibility, discipline, and empathy forged through collective struggle. To preserve the middle-class caricature of youth as aimless, self-serving, and unreliable, it becomes essential that they not be shown to be confrontated with class struggle. This is precisely the path the filmmaker has chosen: by omitting any encounter with collective resistance, the film ensures that its protagonist remains trapped within a framework that validates bourgeois prejudices rather than illuminating social truth.

Bahuchithawadiya shares a great deal with the postmodern cinema that has emerged internationally in recent decades—films that purport to critique society by depicting its filth and moral decay, but which in reality offer no understanding of why things are the way they are, and certainly no path forward. These are not works of art that cognize life in its fullness and movement—but snapshots of despair, stripped of causality and agency.

One would compare this to a film like Dharmasena Pathiraja’s Ahas Gauwa (1974), where the main character Wije is shaped by his encounters with the working class. That film ends not with resignation, but with the protagonist joining a trade union struggle, suggesting a transformation in consciousness. Or consider Boodee Keerthisena’s Mille Soya (2004), which, while also centered on the desire to migrate, does not present its characters as predators or cowards, but as desperate and conflicted individuals shaped by historical pressures. In these works, characters evolve, struggle, and relate to the social forces around them. They are alive in history. In today’s society, gripped by deep crisis, a heightened degree of class resistance is not only inevitable but increasingly evident.

Sasitha—so too his roommate—is not shown looking for work: he submits no job applications. He engages in no political talk at all. He has no interest in news. He speaks of migrating to Europe but takes no meaningful steps to do so. The film ends as it began: in stasis. This is not an artistic exploration of paralysis, but a refusal to engage with reality. Real young people in Sri Lanka today are not simply wallowing in nihilism. They are searching for work, forming relationships, joining protests, and trying to understand their place in a collapsing world. Dewapriya‘s Sasitha is not a representation of this generation; he is a libel against it.

Commenting on the depiction of unemployed youth in Take Me Somewhere Nice (2019), written and directed by Ena Sendijarević, David Walsh observes that the filmmaker “underestimates the extent to which the younger generation globally is still at sea, looking for a new orientation, for some stable, coherent political and moral reference point. Many young people, refugees or not, from the Balkans or not, are ‘in-between’ at present, disgusted by the existing set-up and not yet having found an alternative. This ‘in-between-ness’ is bound up with the ‘on-the-eve’ quality of the present moment.”

Walsh’s comment is equally applicable to Dewapriya and his approach in his film. Bahuchithawadiya captures the uncertainty of youth but fails to grasp the transitional, searching character of that uncertainty—its link to a broader historical moment in which masses of young people are questioning the existing order and beginning to look for alternatives.

Moreover, the film is an ideological fodder to the petty-bourgeois strata from which it emerges. It confirms their defeatist view that the poor and unemployed are to blame for their own fate, that they are lazy, treacherous, corrupt, and oversexed. It paints the working class not as the agent of social transformation, but as a cesspool of moral degradation. The youth are not portrayed sympathetically. In this way, the film serves the ideological needs of those who have no intention of challenging the status quo. This is the hallmark of postmodern pessimism—a worldview that substitutes irony for resistance and pathology for class analysis.

There are moments in the film that suggest Dewapriya is not without talent. A number of his previous “radio stories” confirm that he is a promising artist. He has a feel for visual composition, a sensitivity to language, and a certain flair for portraying claustrophobic urban life. But these gifts are, at this stage, limited by a worldview shaped by the narrow horizons of a disoriented middle-class layer, a worldview that remains unable to grasp the full social and historical dynamics confronting the working class youth.

A work of art does not need to be optimistic, but it must be truthful. It must seek to reveal the underlying forces that shape human behavior. An artist should not only cognize life, but should attempt to partially lift the veil of future. When he is dissatisfied with today’s reality, he has to see it through the prism of an ideal “tomorrow” and “show man in his ideal”.

As A.K. Voronsky wrote:

“The dream, yearning and longing for man drawn up to his full height has been and continues to be the foundation of the creative work of the best artists” (Art as the Cognition of Life, and the Contemporary World, 1923)

In this sense, art becomes a means of historical cognition. Bahuchithawadiya fails in this task. It is a film that flinches from the real struggles of our time and retreats into a cold, contemptuous portrait of human failure.

In the final analysis, Bahuchithawadiya is not a film about youth, but about the inability of a certain social layer to comprehend the youth—to see in them not just a mirror of society’s decay, but the potential for its renewal. That is the tragedy of this film.