By Sanjaya Wilson Jayasekera

We are posting here a brief obituary of Sri Lanka’s veteran actress Malini Fonseka, written by comrade Sanjaya Jayasekera and published on his personal website and social media on 25 May 2025. This articles was also published by the daily newspaper themorning.lk Here. Nearly six-decade of the cinematic career of actress Fonseka deserves a full and extended review.

The demise of actress Malini Fonseka on May 24, 2025, marks the end of a cinematic epoch. She is undoubtedly the “Queen of Sinhala Cinema,” as she has been often referred to by millions of her fans, aged and young. Nearly six-decade of her career was not a simple arc of celebrity, but a deep and continuous cinematic identification with the lives of ordinary people, especially women, under the weight of history, patriarchy, backwardness and class oppression. In a country where cinema often struggles between the tides of commercialism, populism, nationalism and repression, Fonseka remained a moral and aesthetic lodestar, truthfully imbuing her characters with emotion, quiet resistance, and tragic insight.

To merely describe Fonseka as a beloved actress is to evade the seriousness of her contribution. She was an artist of social consciousness—her performances bore the weight of Sri Lanka’s post-independence traumas, its unfulfilled democratic promises, and the contradictions of a backward capitalist society pressing in from every side.

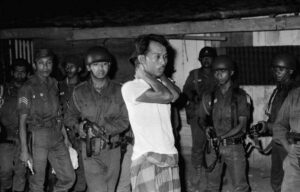

In Lester James Peries’ Nidhanaya (1972), one of the greatest Sri Lankan films ever made, Fonseka plays the innocent, ill-fated woman preyed upon by a man whose wealth and obsession lead to murder. Her character is not merely a victim but a mirror held up to a crumbling feudal order. Fonseka conveys, through silence and subtle gestures, a person slowly awakening to the forces arrayed against her. Her sacrifice is not just personal—it is metaphorically the death of innocence in a society entrapped by its own past.

In Beddegama (1980), based on Leonard Woolf’s The Village in the Jungle, Fonseka as Punchi Menika inhabits a world of colonial exploitation and rural destitution. This is not melodrama but precise, economical realism. Fonseka does not “perform” poverty and female endurance—she lives it. Her face, increasingly lined by anxiety and despair, communicates the pain of a society ground down by injustice, hunger and disease, made worse by the cruelty of an indifferent state.

Equally remarkable is her performance in Dharmasena Pathiraja’s Bambaru Avith (1978). In this film, Fonseka delivers one of her most restrained yet potent performances of the role of a young lady in a coastal village caught in the maelstrom of social disintegration and the predatory arrival of urban outsiders. Fonseka’s portrayal is marked by an acute sensitivity to the class tensions simmering beneath the film’s surface. Her role is not simply a symbol of rural innocence but a deeply aware, emotionally complex figure who senses the destruction bearing down on her community. In a film that critiques both the romanticization of village life and the corrosive effects of capitalist intrusion, Fonseka embodies the silent tragedy of a society being commodified. With minimal dialogue and subtle expressions, she gracefully communicates despair, resignation, and the quiet resistance of a woman rooted in her world but unable to halt its unraveling.

In Akasa Kusum (2008), directed by Prasanna Vithanage, as Sandhya Rani, a faded film star confronting the ruins of her career and personal life, Fonseka embodies the alienation and disillusionment of an artist discarded by an industry that once idolized her, and without any social insurance. The film alludes to the stardom of Fonseka herself. Vithanage’s film, while ostensibly a character study, inadvertently exposes the broader social decay under capitalism, where cultural memory is short and individuals are reduced to commodities. Fonseka’s restrained yet deeply expressive performance underscores the tragedy of a woman whose labor and talent have been exploited, then abandoned—a microcosm of the artists’ precarious existence in a profit-driven system. The film’s critique of bleak nostalgia and the fleeting nature of fame resonates with the broader crisis of art under conditions where everything, including human creativity, is subordinated to the market. While Akasa Kusum does not explicitly engage with class struggle, Fonseka’s portrayal of Sandhya’s isolation and resilience speaks to the perseverance of ordinary people amid systemic indifference.

Fonseka’s performances in a wide range of other films—including Eya Dan Loku Lamayek (1977), Siripala Saha Ranmenika (1978), Ektamge (1980) and Yasa Isuru (1982) —as well as in teledramas such as Pitagamkarayo (1997), are etched into the collective memory of Sri Lankan audiences. In each of these roles, she brought to life women shaped by their social conditions, investing them with dignity, emotional depth, and a quiet intensity that transcended the screen. Whether portraying the struggles of urban motherhood, the constraints of poverty, caste and patriarchy, or the conflicted desires of village life, the veteran actress was able to truthfully reveal the deeper realities of the society around her.

Like several other leading actors of her generation, Fonseka was a significant historical product of her time. By the 1970s, Bollywood’s musical and melodramatic cinema exerted a powerful influence over Sri Lankan audiences, who flocked to theaters largely drawn by star appeal. Sinhala cinema, still emerging as a serious artistic medium, had to contend with the commercial dominance of Indian films. Fonseka’s rise to stardom was not merely a matter of charishma; her compelling screen presence, combined with the emotional depth and authenticity she brought to nearly every role, enabled her to capture the imagination of a broad audience. In doing so, she played a crucial role in affirming the cultural legitimacy and artistic potential of Sinhala-language cinema, as part of the world cinema.

Fonseka’s popularity, unmatched for decades, was not simply built on glamour but on the deep compassion she earned. For the oppressed, she did not offer escapism; she offered recognition and fight. Her status as “queen” is a title she earned from the sincere presentation of the struggles of those who loved her.

Her art reminds us of what cinema can be: a site of conscience, a record of the oppressed, and a spark of rebellion. She belongs to that rare tradition of film actors—like Smita Patil, Giulietta Masina, and Liv Ullmann—who made of their bodies and voices a battlefield of history.

In the later years of her life, Fonseka became associated with the bourgeois nationalist establishment, serving as a Member of Parliament from 2010 to 2015 under the government of then-President Mahinda Rajapaksa. While no political concessions can be made to her alignment with Sinhala nationalist politics, her profound contributions to cinema—rooted in social realism and the depiction of the oppressed—remain of enduring artistic and historical value. Her body of work deserves to be critically appreciated, drawn inspiration from and preserved as a significant part of both Sri Lankan and world cinema.

Malini Fonseka will be remembered not merely as a great actress, but as an artist of the oppressed masses. Her characters will continue to live, as all genuine art does, not only in memory but in the continuing struggles of those they represented.