Weekly Political Report — Week Ending 21 February 2026

This political report for the week of February 15–21, 2026, is compiled based on coverage from the World Socialist Web Site (WSWS.org).

I. Imperialism and War

US War Preparations Against Iran

The most urgent development of the week is the accelerating US preparation for war against Iran. Washington drew up plans for “leadership change” and “targeting of individuals” in any Iran strike, while US forces were repositioned in the region in readiness for what military planners described as a “sustained, weeks-long” campaign.[1] The USS Abraham Lincoln carrier strike group was already operational in the Arabian Sea and the USS Gerald R. Ford — the world’s largest warship — transited the Strait of Gibraltar and entered the Mediterranean. More than 50 fighter jets, two carrier strike groups and dozens of refueling tankers were deployed.[2]

Trump and Netanyahu held a three-hour war council at the White House to coordinate strategy.[3] European imperialist powers — Britain, Germany and others — lined up behind regime-change in Tehran. This is not a bilateral US-Iran crisis but an expression of inter-imperialist competition for regional dominance, energy resources and geostrategic control. The working class internationally must oppose this war drive through mass mobilisation, linking anti-war demands to opposition to the domestic austerity imposed to finance rearmament.

Gaza: Slaughter Continues Amid Diplomatic Theatre

Israeli air strikes killed 12 Palestinians on the eve of Trump’s “Board of Peace” meeting — a cynical exercise in diplomatic theatre that masks Washington’s unconditional backing for genocide. Eyewitness testimony from Gaza published during the week, recounting the brutal killing of a Palestinian child and the systematic denial of medical care, cuts through every abstraction and exposes the class basis of imperialist violence. More than 100 international film artists condemned the Berlinale festival for censoring artists who oppose Israel’s actions, while Germany’s parliament president conducted an embedded visit to Gaza, signalling Berlin’s endorsement of the genocidal campaign. European institutions are not neutral bystanders — they are complicit partners in imperialist crime.

Militarisation of Europe

The heads of British and German armed forces called this week for “whole-of-society” mobilisation and massive increases in defence spending, demanding that Europe’s populations be made ready for war. Factories in ailing industrial regions of Berlin are being repurposed for military weapons production. This is a declaration of class war: rearmament will be paid for by workers through wage cuts, service reductions and political repression. The working class must respond with international anti-war mobilisation and rank-and-file committees to resist the austerity that militarisation demands.

II. Authoritarian Consolidation and State Repression

ICE: Spearhead for Dictatorship

ICE raids intensified across the United States during the week. Masked ICE agents conducted operations outside GM’s Factory Zero in Detroit; two Amazon Flex drivers were abducted during enforcement actions; a two-month-old infant was deported after falling gravely ill in a south Texas detention facility; and a former Cass Tech student, Alcides Caceres, was held in what lawyers described as an illegal “domestic Guantánamo.” Immigration attorney Eric Lee warned that the mass detention infrastructure being constructed by the Trump administration is the spearhead of a broader drive toward authoritarianism and domestic dictatorship.

Pennsylvania high school students who walked out in protest against ICE operations were met with violent police repression. The UAW bureaucracy remained silent as agents operated outside Factory Zero. This silence is not accidental — it reflects the union apparatus’s accommodation to state and employer power. The defence of immigrant workers is inseparable from the defence of the entire working class, and requires workplace committees prepared to shut down production in defence of coworkers.

Trump’s Assault on Democratic Rights

Trump signalled plans for an executive order restricting voting procedures ahead of midterm elections. The jailing of a former South Korean president for coup-related offences, contrasted with Trump’s continued occupation of the White House, illustrates the decomposition of bourgeois democratic forms under the weight of capitalist crisis. These are not isolated authoritarian manoeuvres — they form part of a systematic consolidation of executive power that requires mass, independent working-class political resistance, including preparedness for a general strike.

State Repression Internationally

In Hungary, German anti-fascist Maja T. was sentenced to eight years in prison in a politically orchestrated show trial. France’s mainstream politics lurched further right following the death of a prominent fascist figure. The ANC government in South Africa moved to deploy the army domestically to suppress worker unrest. Russia banned WhatsApp. The Albanese Labor government in Australia moved to bar women and children interned in Syria from returning home. France’s human rights commission documented torture, mass detentions and systematic discrimination against the Kanak people during 2024 unrest in New Caledonia. The common thread is the international capitalist class reaching for repression as its preferred instrument of social management.

III. Global Economy and Corporate Restructuring

IMF Presses China; Inter-Imperialist Economic Rivalry Sharpens

The IMF this week called on China to halve industrial subsidies from 4 to 2 percent of GDP and pivot from export-led manufacturing to domestic consumption, warning of international “spillovers” from China’s growing trade surplus and rising share of global manufacturing. Beijing rejected the framing, defending its competitiveness as innovation-driven — signalling that no major course correction will follow and that economic confrontation, above all with Washington, will intensify. The IMF’s prescriptions are not neutral technical advice but coordinated imperialist pressure to constrain China’s industrial rise. Workers in China and internationally must reject both IMF-dictated restructuring and nationalist protectionism as twin instruments of rival capitalist classes.

Wages, Jobs and Corporate Profits

The week’s economic reporting exposed the class content of the global “cost of living crisis” with precision. In Australia, new data confirmed real wages have fallen to their lowest level in 15 years — nominal growth of 3.4 percent against inflation of 3.8 percent — while major corporations simultaneously announced record profits and accelerated job cuts. Volkswagen announced plans to impose a 20 percent cost reduction across all its brands by 2028, equivalent to €60 billion annually, with entire plant closures envisaged — an escalation beyond the 35,000 job cuts and real wage reductions of up to 18 percent already certified by IG Metall in December 2024. UPS simultaneously prepared a second round of driver buyouts ahead of 30,000 planned layoffs in 2026, while the Los Angeles Unified School District moved to eliminate hundreds of positions. The US Department of Labor’s annual tally recorded 5,070 workers killed on the job in 2024 — not accidents but the structural outcome of deregulation, staffing cuts and production speedups driven by the profit motive, with union bureaucracies and weakened regulators normalising lethal conditions. In Argentina, Javier Milei’s Labour Modernisation Law — slashing protections and facilitating mass layoffs — passed despite a national general strike, as the CGT and allied bureaucracies deliberately confined action to a symbolic 24-hour stoppage. India’s BJP budget raised defence spending by approximately 15 percent while cutting the share of social expenditure and shifting rural relief costs onto cash-strapped states, combining military build-up with attacks on workers’ rights through new labour “reforms.”

Militarisation of Production and Civilian Infrastructure

The economic offensive is inseparable from the drive toward war. In Berlin, factories in declining industrial regions are being bought up and retooled for military weapons production. Walter Reed military hospital formalised an agreement with Kaiser Permanente to coordinate mass-casualty care for future wars — the subordination of civilian healthcare to military contingency planning. Veolia, the multinational water services corporation, was implicated in New Zealand’s wastewater crisis, exposing how the privatisation of essential infrastructure produces environmental disaster and social harm. Across every sector, the picture is the same: capital extracts record profits, destroys jobs, slashes wages, converts civilian production to military ends — and charges the working class for it all. The working class must reject the austerity that funds militarism, build independent rank-and-file committees to resist corporate restructuring, and link these struggles across borders and sectors into a unified international movement.

IV. Austerity and Economic Warfare

India: Guns Before Butter

The BJP government’s 2026–27 budget raised defence spending by approximately 15 percent while cutting the share of social spending and shifting rural relief costs to debt-ridden states. Corporate subsidies and infrastructure CAPEX were expanded alongside labour “reforms” that erode workers’ rights. The budget encapsulates capitalism’s response to global strategic instability: privilege military capacity and corporate accumulation while attacking living standards. The tens of millions who joined a one-day national strike against Modi’s class war assault the prior week demonstrated the scale of mass anger — but the Stalinist-led federations channelled that energy toward bourgeois electoral alternatives rather than independent working-class struggle.

Argentina: Bureaucracy Enables Historic Counterreform

In Argentina, a 24-hour general strike failed to halt the passage of Javier Milei’s Labour Modernisation Law, which slashes worker protections and facilitates mass layoffs.[4] The CGT and allied bureaucracies deliberately bottled up the struggle, enabling the ruling class to ram through anti-labour reforms that constitute the most sweeping attack on working-class rights in decades. The lesson is unambiguous: a single-day strike controlled by bureaucracies that refuse to paralyse production is not a general strike — it is a safety valve.

Volkswagen: 20 Percent Cost Reduction Across All Brands

Volkswagen announced a corporate plan to cut costs by 20 percent across all brands, threatening plant closures, job losses and intensified speed-ups. Co-management institutions and union bureaucracies will facilitate these cuts unless workers build rank-and-file committees to coordinate cross-plant resistance and international solidarity across global supply chains.

Falling Real Wages and Public Service Collapse

Real wages continued to fall in Australia. Seven Los Angeles County public health clinics announced the end of clinical services. The Los Angeles school district moved to eliminate hundreds of positions. Washington D.C. declared a public emergency after a major sewer collapse. The US Department of Labor reported 5,070 workers killed on the job in 2024 — an annual death toll that reflects not accidents but the structural outcome of capitalism’s drive for profit under conditions of deregulation and staffing cuts.

V. Class Struggle and Bureaucratic Betrayal

US Healthcare: The Central Arena of Struggle

The Kaiser Permanente strike of 31,000 healthcare workers entered its fourth week, with operating engineers from IUOE Local 501 joining the action, broadening the dispute to technical trades whose withdrawal threatens hospital functioning.[5] Nurses at NewYork-Presbyterian simultaneously defied the New York State Nurses Association’s attempt to impose a second sellout agreement through a rushed snap ratification vote. Rank-and-file nurses had overwhelmingly rejected the first tentative agreement — nearly 74 percent voted it down; the bureaucracy responded by engineering a second vote under conditions designed to maximise management-friendly outcomes and minimise membership oversight.[6]

These strikes reveal a healthcare system driven by profit, executive pay and marketisation. The decisive question is whether they remain fragmented or develop into a unified national fight. That depends on the construction of democratic rank-and-file committees across hospitals, unions and regions, capable of coordinating industrial strategy, enforcing strike discipline and expanding the struggle beyond the boundaries set by bureaucratic leaders.

Mexican Auto Parts Workers Occupy Plants

Workers at six First Brands maquiladora plants occupied factories across northern Mexico after mass shutdowns and the firing of over 4,000 employees, physically preventing the removal of machinery.[7] The occupations echo the historic sit-down strikes of the 1930s and demonstrate the willingness of workers to assert direct control over production. This struggle exposes the transnational integration of auto supply chains: UAW bureaucratic nationalism and employer collaboration must be broken by international rank-and-file coordination. UAW rank-and-file candidate Will Lehman publicly backed the occupations and linked them to his campaign for democratic restructuring of the union.[8]

San Francisco Teachers and the NYSNA Sellout

The UESF bureaucracy in San Francisco ended a four-day strike with a tentative agreement containing minimal raises, a no-strike clause, and acceptance of austerity parameters — while the district warned of imminent budget cuts and layoffs. In New York, the NYSNA forced a second snap vote on a contract for NewYork-Presbyterian nurses that fails to secure safe staffing or meaningful job protections. Both episodes exemplify the same dynamic: union bureaucracies choreograph controlled stoppages that dissipate militant momentum while accepting the fundamental terms of the employers’ austerity agenda.

BP Whiting Refinery Workers and the USW Betrayal

Workers at BP’s Whiting refinery, who voted 98 percent for strike authorisation, were left on the job under day-to-day extensions while the United Steelworkers International negotiated a national pattern deal in secret. Workers publicly denounced the union for isolating their facility. The USW’s pattern deals normalise concessions, fragment industrial power and prevent the coordinated national strike that alone can defend wages, jobs and safety.

Royal Mail: CWU as Industrial Enforcer

At Royal Mail’s Mount Pleasant Mail Centre in London, workers circulated the Postal Workers Rank-and-File Committee statement exposing the CWU leadership’s role in implementing the Optimised Delivery Model — a restructuring scheme that extends delivery spans, intensifies workloads and entrenches two-tier pay. The CWU has disappeared into closed-door talks with management and the EP Group. The breakdown of service is not the result of operational difficulties but of deliberate asset-stripping backed by the union apparatus. The only path forward is democratically controlled rank-and-file committees that restore power to workers on the shop floor.

VI. Elite Criminality and Political Decay

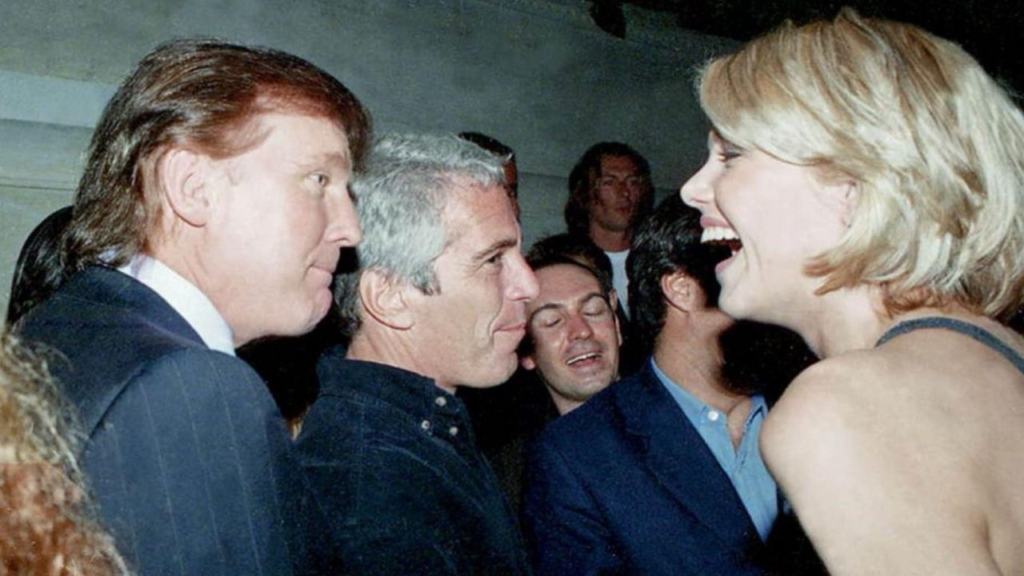

The Epstein Files and the Monarchy

Former Prince Andrew was arrested on suspicion of Misconduct in Public Office after documents from the Jeffrey Epstein releases linked him to the sharing of confidential information and access with Epstein’s network. Searches were conducted at royal residences.[9] Further documents forced high-profile billionaires, corporate lawyers and executives to resign. US corporate media simultaneously framed public outrage over the files as “conspiracy theories,” protecting elite networks from accountability.[10]

The arrest and the ongoing revelations do not represent justice — they represent factional damage control within a decomposing ruling class. The Epstein files expose the intimate integration of the monarchy, the state and the global financial oligarchy.[11] Newly released documents also confirmed Noam Chomsky’s extensive personal accommodation with Epstein — travel on his plane, stays at his properties, private counsel during Epstein’s 2019 media crisis — exposing the capacity of sections of the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia to be co-opted by the ruling class while posturing as moral critics.[12] The lesson: meaningful opposition to oligarchy cannot rest on celebrity dissent. It requires independent working-class organisation.

VII. The Political Bankruptcy of Reformism

Fortress Europe: Social Democracy’s Capitulation

The European Parliament approved a revised Asylum Procedure Regulation and Return Border Procedure Regulation, creating an EU-level list of “safe countries of origin” (including Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, India, Bangladesh, Colombia and Kosovo) and expanding powers to deport migrants to external “return hubs.”[13] The measures passed with notable defections and abstentions from social-democratic deputies in Denmark, Malta, Romania and Sweden. This is not a technocratic tightening of asylum law but a political offensive — the continentalisation of “Fortress Europe.” Social-democratic parties have abandoned any substantive defence of migrants or democratic rights, aligning with conservatives and the far right to militarise borders and outsource repression. The measures serve capitalist interests: disciplining labour markets, deflecting social unrest into xenophobia and consolidating the authoritarian tools the ruling class requires for class war at home.

The Pseudo-Left as Bureaucratic Enforcer

The DSA launched personal attacks and smears against UAW rank-and-file candidate Will Lehman, whose campaign for union president — built on abolishing the Solidarity House bureaucracy and establishing rank-and-file committees — drew wide grassroots support from autoworkers in the US and Canada. The DSA’s intervention exposes the pseudo-left’s function: to police acceptable labour politics and divert militancy into safe institutional channels. In Catalonia, union bureaucracies and the regional government moved rapidly after a mass teachers’ strike to contain rank-and-file anger through negotiated settlements. New York Mayor Zohran Mamdani threatened a 9.5 percent property tax rise on workers while shelving rental voucher expansions and accommodating Governor Hochul — the DSA mayor managing capitalist budgets rather than challenging Wall Street.[14]

David North’s Lectures in Ankara

David North, chairman of the International Editorial Board of the WSWS and national chairman of the Socialist Equality Party (US), delivered lectures at Bilkent University and METU in Ankara titled “Where is America headed? The American volcano and the global tsunami.” The lectures connected the US political crisis — domestic democratic erosion, rising inequality, aggressive imperialism — to Trotsky’s analysis of the epoch and the necessity of world socialist revolution. The strategic tasks posed are clear: build political independence from bourgeois institutions, construct rank-and-file and party-building organs across borders, and prepare the working class to lead the struggle against war, austerity and dictatorship.

***

The developments of this week confirm the central thesis advanced by the International Committee of the Fourth International: capitalist crisis produces simultaneous austerity, repression and imperialist war, while union bureaucracies and reformist parties function as the enforcers of the ruling class within the workers’ movement. The necessary answer is the independent, international organisation of the working class around a Trotskyist programme — rank-and-file committees in workplaces and schools, coordinated across national boundaries, and the construction of sections of the Fourth International capable of providing revolutionary leadership.

—theSocialist.lk

References:

[1] “US draws up plans for ‘leadership change’ and ‘targeting individuals’ in Iran strike,” WSWS, 21 February 2026. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2026/02/21/abbz-f21.html

[2]: “US forces in position for illegal attack on Iran,” WSWS, 20 February 2026. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2026/02/20/lhql-f20.html

[3]: “Trump and Netanyahu hold Iran war conclave,” WSWS, 12 February 2026. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2026/02/12/wali-f12.html

[4]: “National strike in Argentina fails to halt historic labor counterreform and mass layoffs,” WSWS, 21 February 2026. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2026/02/21/bdeb-f21.html

[5]: “Expanding nurses strikes in California and New York raise need for unified struggle,” WSWS, 18 February 2026. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2026/02/18/uyrg-f18.html

[6]: “New York nurses in ‘uprising’ against union boss’s attempts to sabotage strike,” WSWS, 18 February 2026. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2026/02/18/rtmw-f18.html

[7]: “Auto parts workers occupy plants across northern Mexico after 4,000 jobs cut,” WSWS, 18 February 2026. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2026/02/18/whph-f18.html

[8]: “Will Lehman backs plant occupations by Mexican auto parts workers against mass layoffs,” WSWS, 20 February 2026. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2026/02/20/jczl-f20.html

[9]: “Former prince Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor arrested in Epstein investigation,” WSWS, 19 February 2026. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2026/02/19/xxkq-f19.html

[10]: “US corporate media slanders anger over Epstein cover-up as ‘conspiracy theories’,” WSWS, 18 February 2026. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2026/02/18/pbbm-f18.html

[11]: “Andrew’s arrest, the British monarchy, and the international oligarchy,” WSWS, 20 February 2026. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2026/02/20/zcdn-f20.html

[12]: “Noam Chomsky’s contemptible friendship with Jeffrey Epstein,” WSWS, 15 February 2026. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2026/02/15/f305-f15.html

[13] “Sections of European social democrats vote with conservatives and far-right to pass anti-migrant policies,” WSWS, 15 February 2026. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2026/02/15/zvsc-f15.html

[14] Zohran Mamdani threatens to increase property tax on New York City workers” WSWS, 19 February 2026

Weekly Political Report — Week Ending 21 February 2026 Read More »